In my search for a sense of inner balance — what the Japanese call 中心(ちゅうしん / chūshin), literally the “center of the heart-mind” — I’ve found myself drawn toward a tradition that is both ancient and deeply disarming: the 公案(こうあん / kōan). These are not riddles in the conventional sense. They do not come with clever answers. A kōan is a saying, a question, or a brief exchange used in 禅(ぜん / Zen) Buddhism to challenge our habitual ways of thinking.

The character 公(こう / kō) means “public” — open, universal, impartial. 案(あん / an) means “case” or “document.” In its original Chinese legal context, 公案 referred to a public legal case or official record. But in the hands of Zen masters, it transformed: the “public case” became a spiritual challenge, a confrontation with truth. A kōan is not meant to be solved, but lived — a kind of intimate encounter with reality that resists logic and defies ego.

A traditional kōan might ask:

「父母未生以前の本来の面目とは何か?」

(Fubo mishō izen no honrai no menmoku to wa nanika?)

“What is your original face before your father and mother were born?”

At first glance, this sounds like it refers to your parents — but in Zen language, it’s more symbolic than literal. 父母未生以前(ふぼみしょういぜん / fubo mishō izen) means “before your father and mother were born,” but it actually points to your own existence before birth — before identity, thought, form, or even consciousness. It’s not about genetics or family lineage; it’s about the 本来の面目(ほんらいのめんもく / honrai no menmoku), your “original face” — your true nature before you were shaped by the world.

This kōan, like many others, isn’t meant to be answered logically. It’s an invitation to look inward, beyond what the thinking mind can grasp.

This strange question isn’t metaphorical. It points to something beyond personality, beyond memory, even beyond life itself. The phrase 本来の面目(ほんらいのめんもく / honrai no menmoku) literally means “true/original face.” It invites us to consider: Who — or what — are we, before we are named, shaped, or remembered?

The practice of kōan began in China during the 唐(とう / Tō) dynasty, in the 7th to 9th centuries, as the 禅宗(ぜんしゅう / zenshū), or Chan Buddhist tradition, emerged. Masters and students recorded encounters — often spontaneous, paradoxical, and raw — that pointed directly to awakening. These teachings were brought to 日本(にほん / Nihon), where the 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう / Rinzai-shū) school developed a highly structured system of kōan meditation. During the 江戸時代(えどじだい / Edo period), the Zen monk 白隠(はくいん / Hakuin) reformed and revitalized this system, making kōan training central to Japanese Rinzai Zen. What was once a cryptic story or question became a rigorous spiritual path.

Today, kōan are still practiced in monasteries — but more and more, laypeople are also turning to them. Not to gain esoteric knowledge, but to return to something essential. In a world saturated with answers, explanations, and noise, the kōan invites us back to silence.

Why am I choosing to work with kōan? Because I want to learn how to live without needing to solve. I want to become more comfortable not knowing. The kōan doesn’t comfort or explain. It unravels. It cuts through patterns of thought and demands a direct meeting with the present moment.

So how does one approach a kōan? You begin simply. Choose one. Let it choose you. Sit with it — in 坐禅(ざぜん / zazen), or just in the rhythm of daily life. Don’t try to analyze it. A kōan isn’t a puzzle to be worked out. Instead, carry it with you. Let it echo in ordinary moments — in the sound of footsteps, the pause before a breath. And slowly, without force, something inside begins to shift.

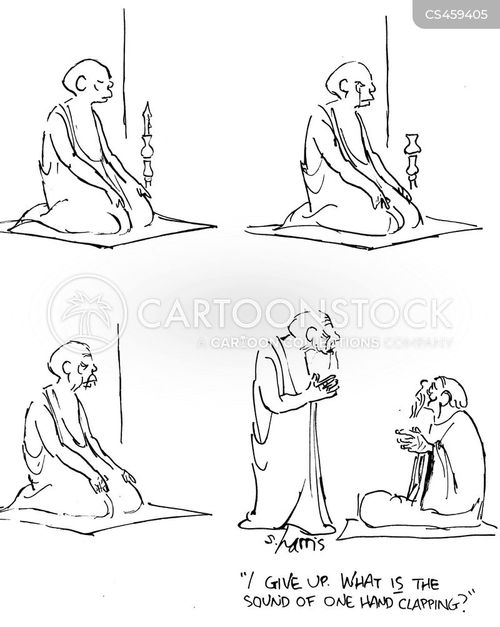

Here is one kōan, offered without explanation:

「隻手の声とは何か?」

(Sekishū no koe to wa nanika?)

“What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

Let it accompany you — gently, wordlessly.

Forget it. Remember it. Carry it. Sit with it.

Let it speak not to the mind, but through silence.